61 Seizure Disorders

61.1 Introduction

The term seizure vaguely refers to anything that “seizes” or “takes hold” of a person. These may be epileptic or non-epileptic events. In this chapter, unless otherwise specified, the term seizure is used to refer to epileptic events.

61.2 Definitions

61.2.1 Seizures

The International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) defines epileptic seizure as a transient occurrence of signs and/or symptoms due to abnormal, excessive, or synchronous neuronal activity in the brain. These may manifest as paroxysmal motor, sensory, autonomic, and/or behavioral or cognitive function abnormalities or impaired consciousness.

61.2.2 Convulsions

These are the motor manifestations of a seizure. These include tonic (stiffening), clonic (jerking), myoclonic (massive jerking), vibratory (trembling), or hypermotor (thrashing about). Seizures with no motor manifestations are termed non-convulsive and include motor arrest, e.g., unresponsive stare or drop attacks. Sensory disturbances during a seizure may include visual, auditory, or tactile disturbances. Some patients may describe changes in smell or taste.

Non-epileptic seizures in children include many events such as cardiac syncope, vasovagal syncope, breath-holding spells, infantile gratification, shuddering spells, etc. These are sometimes referred to as seizure mimics.

61.3 Classification of Seizures

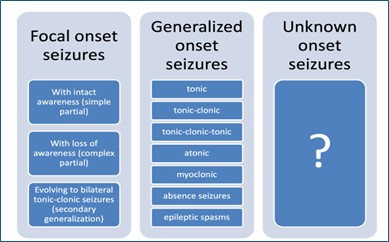

The ILAE published its most recent classification of seizures in 2017. In this classification, seizures are broadly classified based on their onset within the brain as focal, generalized, or unknown onset.

- Focal-onset seizures originate from a focus within one hemisphere.

- Generalized-onset seizures originate from both hemispheres.

- Unknown onset – where the onset is not known at the time of the evaluation.

Focal-onset seizures (previously known as partial seizures) are further subclassified based on whether awareness is preserved or lost during the seizure and secondary generalization.

- Focal seizures with intact awareness (or focal aware seizures): These are focal seizures in which awareness is preserved. This was previously known as simple partial seizures.

- Focal seizures with loss of awareness (or focal unaware seizures): These are focal seizures in which awareness is lost during the event. They were previously referred to as complex partial seizures.

- Focal seizures evolving into bilateral tonic-clonic seizures: These are focal seizures that go on to become generalized. They were previously referred to as focal seizures with secondary generalization.

Generalised-onset seizures are further subclassified based on their manifestations as:

- Clonic seizures: having repetitive jerky movements.

- Tonic seizures: characterised by increased tone.

- Tonic-clonic seizures: They have two phases: a tonic phase and a clonic phase.

- Tonic-clonic-tonic, or other combinations

- Atonic seizures: These are characterized by loss of muscle tone, leading to drop attacks.

- Myoclonic seizures: These are characterized by sudden jerks of a group of muscles.

- Absence seizures: These are characterized by blank stares during which the patient loses awareness. They may be associated with lip-smacking or eyelid fluttering. A typical absence seizure starts abruptly, lasts about 5-15 seconds, and ends abruptly with no postictal events. An atypical absence may last >15 seconds or may have a slow recovery.

- Epileptic spasms: These are characterized by repetitive flexor (or extensor) jerks of the limbs and trunk, occurring in clusters.

61.4 Febrile seizures

61.4.1 Definition

A febrile seizure is accompanied by fever in a child aged 6 months to 6 years without intracranial infection/inflammation [ref]. It affects about 3% of all children between 6 months and 6 years old.

Biological Basis

The exact mechanism leading to febrile seizures is not clearly understood; biology is related to the immature brain in young children, fever, and genetic predisposition. The fever activates the cytokine networks (IL-1 alpha, IL-1 beta), increasing neuronal excitability. There is a complex inheritance involving multiple genes and environmental factors for children with genetic predisposition. Monozygotic twins have a higher concordance rate than dizygotic twins.

The risk for a first febrile seizure in a child is increased in those with

- Delayed neonatal hospital discharge

- Slow neurological development as judged by the parent

- Family history of febrile seizures (especially in a first-degree relative)

- Attendance at day care

61.4.2 Etiology

Common causes of febrile seizures include malaria, URTI, otitis media, pharyngitis, transient viral infections, and gastroenteritis. Some children develop a fever following vaccination with whole-cell DPT or measles vaccine.

61.4.3 Classification

Febrile seizures are classified as simple or complex. Table 61.1 below shows the differences between simple and complex febrile seizures.

| Feature | Simple febrile seizure | Complex febrile seizure |

|---|---|---|

| Seizure type | Generalized | Maybe focal |

| Duration | Brief (<15 min) | Prolonged |

| Number of episodes | Single episode during the febrile illness | Repeated episodes in the same illness |

| Outcomes | Do not cause brain damage | Increased risk of brain damage |

61.4.4 Risk of recurrence

In children with febrile seizures, the risk factors for recurrence are

- Young age at the time of the first febrile seizure (< 15 months)

- Family history of febrile seizures (first-degree relative)

- Low temperature at the time of the seizure (< 40 degrees)

- Short duration of illness before the seizure [Berg et al, 1997]

Having a complex febrile seizure and neurologic dysfunction are not consistent predictors of recurrence.

61.4.5 Risk of subsequent epilepsy

The risk of epilepsy in children with febrile seizures is slightly higher than the incidence in the general population. The risk is increased with:

- Complex febrile seizures (focal, prolonged, repeated within a single illness)

- Developmental delay or neurologic dysfunction

- Family history of epilepsy

The number of febrile seizures is not a predictor of subsequent epilepsy.

61.4.6 Long-term cognitive and behavioural outcomes

Febrile seizures are “benign”. Studies have shown that children with febrile seizures have the same academic progress, intellect, and behaviour as other children.

61.5 Acute scenarios: prolonged seizures versus status epilepticus

61.5.1 Definitions:

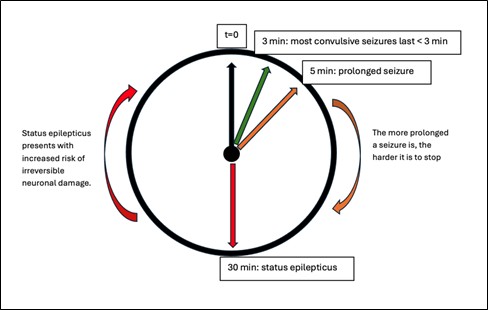

Prolonged seizures: Most convulsive seizures in children are brief (lasting < 3 minutes). However, some may go on beyond 5 minutes. These are termed prolonged seizures.

Status epilepticus, on the other hand, is a prolonged seizure lasting more than 30 minutes or multiple seizures without recovery of consciousness. This definition applies to convulsive seizures. The duration of non-convulsive seizures differs based on the seizure type.

61.5.2 Pathophysiology of status epilepticus

In the initial seizure phase, the body undergoes autoregulation, leading to increased heart rate, cardiac output, and cerebral perfusion. This ensures that there is increased oxygen and glucose delivery to the brain. Also, increased cerebral perfusion helps remove carbon dioxide and metabolic waste, which build up in the brain during seizures. Beyond 30 minutes, this autoregulation breaks down, reducing cardiac output, decreasing systemic blood pressure, and decreasing cerebral perfusion. In the end, there is decreased oxygenation (hypoxia) and buildup of metabolic waste, which trigger a cascade of events with resultant neuronal deaths. This is why it is essential to stop any seizure from progressing into a status epilepticus.

61.5.3 The Do’s and Don’ts in acute scenarios

In the first few minutes of a seizure, it is essential to undertake basic first aid measures to protect the patient. These are termed the Do’s and include:

- Protect the person from injury (eg, remove harmful objects from nearby, cushion their heads, etc.)

- When the seizure is over, gently place the patient in recovery. This positioning aids breathing by ensuring the patient does not choke on their secretions.

- Stay with the patient until the seizure is over.

- Stay calm and reassuring.

Some traditional practices can be harmful and should be discouraged. These are referred to as the Don’ts and include:

- Do not restrain the person’s movements. Forcefully restraining their movement does not stop the seizures and may instead result in needless injuries like fractures and dislocations.

- Do not put anything in their mouth. This could lead to the patient biting on the spoon or spatula and causing damage to their teeth, gums, or palate. Also, please do not put your finger in their mouth. A forceful bite on your figure can lead to severe injuries, including amputation.

- Do not try to move them unless they are in danger.

- Do not give them anything to eat or drink until they fully recover.

- Do not attempt to bring them around. Practices such as pouring cold water on the patient, smearing them with garlic or other noxious substances are harmful and do not stop the seizures.

Indications for bringing the patient to the emergency room include:

- If this is the person’s first seizure.

- If the seizure continues for more than five minutes.

- If one seizure follows another without the person regaining consciousness between seizures.

- If the person is injured.

- If you believe the person needs urgent medical attention.

61.5.4 General principles of management of Prolonged Seizures and Status Epilepticus

In the first 5 minutes, critical interventions should include:

General emergency measures including

- A = airway

- B = breathing

- C = circulation

- D = disability (such as hypoglycemia)

- E = exposure

Check blood glucose and correct hypoglycemia, if present.

Remember the Do’s and Don’ts.

If the seizure persists after 5 minutes, initiate drug management.

- 1st line drugs are benzodiazepines: these commonly include diazepam (rectal/IV, midazolam (buccal/nasal), and lorazepam (IV/rectal). These may be repeated after 10 minutes if the seizure persists.

- 2nd line drugs include phenobarbital (IV), phenytoin (IV), valproate (IV), or levetiracetam (IV).

- 3rd line drugs include anesthetic agents and should be given in the intensive care unit or in a center where the patient’s breathing can be supported. They include thiopentone, propofol, and ketamine. Alternatively, continuous infusions of midazolam or repeated intravenous boluses of phenobarbitone may be used.

This stepwise approach to the management of ongoing seizures is illustrated in Table 61.2 below:

| Time | Action required | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| t = 0 (seizure onset) | Ensure patient’s safety (remember the Do’s and Don’ts) Check the ABCDs.

|

Most seizures will stop on their own within 3 minutes of onset. |

| t = 5 min | Start 1st line pharmacologic treatment with a benzodiazepine. | Commonly used benzodiazepines include:

|

| t = 15 min | If seizure persists to time t = 15 min (10 minutes after the first benzodiazepine), repeat the dose of benzodiazepine. | Benzodiazepines may be repeated once only. Avoid >2 doses of benzodiazepines. |

| t = 25 min | Start the 2nd line pharmacologic treatment. | Commonly used 2nd line drugs are:

|

| t = 40-60 min | Start the 3rd line pharmacologic treatment. | This stage employs anesthetic agents. It should be done in a center where the patient’s breathing can be supported. |

61.5.5 Prognosis of Status Epilepticus in Children

In patients who present with convulsive status epilepticus (CSE), there is a mortality rate of 3-9% within 30 days of the CSE. The mortality rate is worse in low- and middle-income countries.

In those who survive, the neurological sequelae depend on the type and duration of the seizure, the patient’s age, and the underlying etiology.

- Duration of the SE – the single most important determinant of prognosis. Worse outcome for prolonged SE.

- Age – worse neurological sequelae in infants (30% vs. 6% in older children)

- Seizure type – worse outcome for convulsive SE

- Underlying etiology

61.6 Epilepsy

61.6.1 Definition:

Epilepsy is a disease of the brain defined by any of the following conditions:

- At least two unprovoked seizures occurring >24 hours apart.

- One unprovoked seizure and an increased probability of further seizures

- Diagnosis of an epileptic syndrome

It affects over 50 million people worldwide, and 1 in 200 children worldwide.

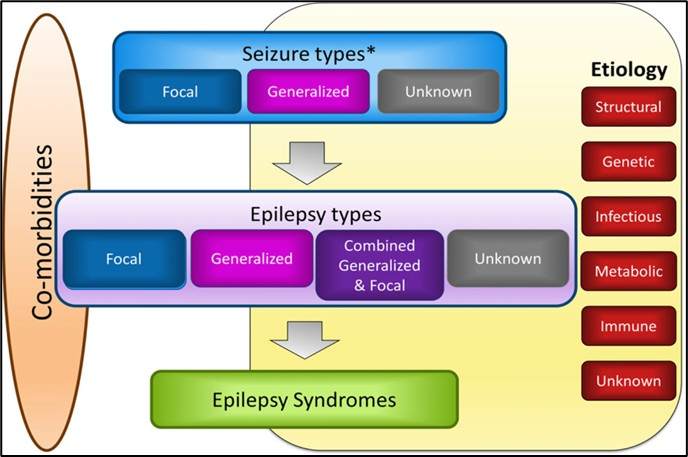

61.6.2 Classification

The ILAE classifies Epilepsy into four main types based on the seizure type (or types) [3]. These are:

- Focal epilepsy

- Generalised epilepsy

- Combined generalised and focal epilepsy

- Epilepsy with unknown seizure type(s)

61.6.3 Causes

All causes of epilepsy can be grouped into six main categories as follows:

- Structural: e.g., lissencephaly, tumours, calcifications, post-stroke, tuberous sclerosis complex, etc.

- Genetic: e.g., familial neonatal seizures, Dravet syndrome, etc.

- Infections: e.g., neurocysticercosis, HIV, post-meningitis, etc.

- Metabolic: e.g., hypoglycemia, electrolyte imbalance, inborn errors of metabolism, vitamin deficiency, etc.

- Immune-mediated: autoimmune encephalitis

- Unknown

61.6.4 Clinical evaluation of the child with epilepsy

In evaluating a child with epilepsy, it is important to obtain a good history, perform a thorough physical examination, and then form a clinical diagnosis (or impression). Investigations are then employed to define the seizure type(s), confirm the clinical diagnosis, identify the underlying etiology, assess the effect of treatment, rule out differential diagnoses, and evaluate comorbidities.

History: An eyewitness account is useful when taking the history of a child with epilepsy. Ask the older child for an account of the episodes. Home videos of the seizure episodes, if available, will complement the history. Key aspects of the seizure history should include:

- Age at onset: This is important in making an epilepsy syndrome diagnosis, as specific epilepsy syndromes have different ages at onset.

- Patient’s baseline neurological status: This may differ from patient to patient and becomes essential in clinical decision-making. For example, the approach to a 3-year-old previously healthy child presenting with seizures will be different from that of a 3-year-old known with cerebral palsy, which will also be different from another 3-year-old known with HIV infection.

- Seizure semiology: This is a detailed description of what happened during the seizure. It is useful to describe the seizure semiology in terms of the different stages, namely the aura (if any), the ictal event, and the postictal event.

- The aura is often a sensory feeling that the patient experiences at the start of the seizure. It is seen in focal-onset seizures. Please note that younger children may not be able to describe an aura.

- Description of the ictal event should include the seizure type (or types), non-motor manifestations (such as behavioral arrest, autonomic dysfunctions, etc.), seizure progression and duration, as well as timing of the events (e.g. shortly after going to sleep, during sleep, on awakening, whilst watching television, etc.).

- Post-ictal events: This is a description of what the patient does after the seizures have stopped. They include events such as falling into deep sleep, changes in behaviour or mood, transient focal weakness (Todd paralysis), etc. Please note that some seizure types (e.g., absence seizures) have abrupt recovery with no post-ictal phase. If there are post-ictal events, the duration should also be noted.

- Developmental/cognitive outcome and co-morbidities: The seizure history should describe the patient’s development and any cognitive fallouts or neurobehavioral comorbidities noted since the onset of the seizures.

- Drug history: This should include a detailed list of all anti-seizure medications used in the past, their contribution to seizure control, and the reason for stopping the drug. Other long-term medications (including herbs) and known allergies should also be described.

- Family history: If other family members have seizures, they should be described in detail, including their relation to the index patient, the seizure type(s), response to treatment, prognosis, etc.

Physical examination

The purpose of the physical examination is to identify risk factors and comorbidities associated with epilepsy and evaluate treatment effectiveness. The initial examination should be comprehensive and include anthropometry, a skin examination for neurocutaneous manifestations, a detailed neurological assessment, a developmental evaluation, and an examination of other systems.

61.6.5 Investigations

It is important to remember that the diagnosis of epilepsy is mostly clinical and that the clinician should not overrely on investigations. However, investigations may be useful in diagnosing epilepsy syndrome, identifying the underlying etiology, assessing the effect of treatment, ruling out differential diagnoses, and evaluating comorbidities.

Basic investigations in the evaluation of the child with epilepsy include:

- Blood counts

- Serum electrolytes

- Liver function and renal function tests

Advanced investigations include:

- Electroencephalogram (EEG)

- Neuroimaging (CT, MRI, SPECT, PET)

- Metabolic screening

- Autoimmune antibody assays

- Molecular genetic testing

61.6.6 Treatment of Epilepsy

The various modalities for treating epilepsy include:

- Medical treatment – traditional and newer Anti-seizure medications (ASMs)

- Hormonal treatment – ACTH or Steroids (Prednisolone) for epileptic spasms

- Vitamins – pyridoxine, folinic acid, and biotin for vitamin-responsive seizures

- Surgical treatment

- Dietary treatment (ketogenic diet)

Medical treatment: This uses traditional or newer Anti-Seizure Medications (ASMs). Not all children with epilepsy require ASM therapy. When needed, ASM selection should be based on seizure type, epilepsy syndrome, and potential side effects. In a low-resource country, availability and affordability should be considered in ASM selection.

Monotherapy is always preferred. However, a few patients will require rational polypharmacy. It is essential to select ASM at the minimum dosage that provides reasonable seizure control with minimal adverse effects. ASM therapy may be discontinued after the patient has had 2 years of seizure freedom.

ASMs have a variety of side effects. Some are dose-related and others are idiosyncratic (non-dose related)

Table 61.3 below shows the traditional anti-seizure medications and their specific indications.

| Drug | Indications | Side Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Phenobarbitone | Status epilepticus Neonatal seizures Epilepsy (both focal and generalized seizures) |

Dose-related: Drowsiness, respiratory depression Idiosyncratic: Rash, Stevens-Johnson syndrome |

| Phenytoin | Status epilepticus Neonatal seizures Peri-operative seizures |

Dose-related: Drowsiness Chronic toxicity: Gingival hyperplasia, coarse facial features, hirsutism, neuropathy, megaloblastic anemia Idiosyncratic: Rash, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, serum sickness |

| Sodium valproate | Broad spectrum Generalized seizures Absence seizures |

Dose-related: Intention tremor, weight gain, polycystic ovaries, teratogenicity (risk of neural tube defects) Idiosyncratic: Hepatic failure, pancreatitis |

| Carbamazepine | Focal seizures Avoid in the absence and myoclonic seizures |

Dose-related: Dizziness, drowsiness, diplopia, ataxia Idiosyncratic: Aplastic anemia, rash, Stevens-Johnson syndrome |

| Ethosuximide | Absence seizures | Dose-related: Dizziness, nausea, weight loss |

Some newer ASMs include Lamotrigine, Topiramate, Levetiracetam, Clonazepam, Clobazam, Vigabatrin (for the treatment of epileptic spasms), Gabapentin, Pregabalin, Felbamate, Oxcarbazepine, Fosphenytoin, Lacosamide, Stiripentol, Tiagabine, and Zonisamide.

Hormonal therapy in the treatment of epilepsy includes:

- Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) – for treatment of epileptic spasms

- Prednisone or prednisolone – for treatment of epileptic spasms, Landau-Kleffner syndrome, etc.

Vitamins may be employed in the treatment of some epilepsies (known as vitamin-responsive or vitamin-dependent seizures). These include:

- Pyridoxine

- Folinic acid

- Biotin

Surgical treatment of epilepsy includes:

- Focal resection

- Lobectomy

- Hemispherectomy

- Corpus callosotomy

- Vagus nerve stimulation

Ketogenic diet: This employs high-fat, low-carbohydrate, and low-protein diets in treating patients with epilepsy. When used, the patient assumes a fasting state, and the brain relies on fatty acids instead of glucose as the primary source of energy. The exact mechanism of action is not known, but it leads to a reduction in seizure frequency and duration. It is effective for all seizure types.

61.7 Epilepsy syndromes

An epilepsy syndrome is defined as a characteristic cluster of clinical and electroencephalographic (EEG) features, often supported by specific etiological findings (structural, genetic, metabolic, immune, and infectious) [ILAE, 2022]

This is to say that some epilepsies can be clustered together as a syndrome based on their features, such as etiology, age at onset, seizure type(s), EEG findings, response to treatment, comorbidities, and long-term prognosis.

Epilepsy syndromes often have age-dependent presentations, may have age-dependent remission, and are usually strongly correlated with other co-morbidities.

Common epilepsy syndromes in children include:

- Early infantile epileptic encephalopathy (Ohtahara syndrome)

- Infantile epileptic spasms syndrome (West syndrome)

- Severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy (Dravet syndrome)

- Lennox-Gastaut syndrome

- Myoclonic astatic epilepsy (Doose syndrome)

- Epilepsy-aphasia (Landau-Kleffner syndrome)

- Childhood absence epilepsy

- Juvenile absence epilepsy

- Self-limiting epilepsy with centro-temporal spikes (previously Benign Rolandic epilepsy)

- Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy

61.8 Neonatal Seizures

61.8.1 Definition

These are seizures in newborns 0-28 days (up to 2 months in clinical practice). They are often poorly organized and difficult to distinguish from normal activity. Clinical patterns include:

- Tonic stiffening of the body

- Tonic deviation of the eyes

- Apnea

- Focal clonic movements of one limb or both limbs on one side

- Myoclonic jerks

- Paroxysmal laughing

- Cycling movement of the limbs

Generalized tonic-clonic movements do not occur in the neonatal period.

The term subtle seizures refers to all the different patterns without tonic or clonic movement of the limbs.

61.8.2 Causes of seizures in neonates by age

Within 24 hours:

- Hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy

- Intrauterine infections

- Intracranial haemorrhage (IVH or SAH)

- Metabolic disorders (commonly pyridoxine deficiency)

24 to 72 hours

- Neonatal sepsis (including meningitis)

- Drug withdrawal

- Metabolic disorders

- Congenital malformations (cerebral dysgenesis)

After 72 hours

- Familial neonatal seizures

- Kernicterus

- Cerebral malformations

- Metabolic disorders

- Congenital malformations (cerebral dysgenesis)

61.8.3 Management of neonatal seizures

- Remember ABCDs

- Phenobarbital is the first-line drug of choice

- Avoid benzodiazepine (unless in a specialist center with respiratory support)

- Repeated Phenobarbital, Phenytoin, or IV infusion of Midazolam may be used as 2nd line or 3rd line

- 3rd line: must be in the NICU where ventilators are available.

- Give vitamins for vitamin-responsive or vitamin-dependent seizures. These include pyridoxine, biotin, and folinic acid.

- Identify and treat the underlying cause.

61.9 Seizure mimics

These are “events” that resemble seizures and may be misdiagnosed as seizures if not carefully evaluated. Common seizure mimics in neonates include:

- Benign sleep myoclonus

- Jitteriness

- Opisthotonos

- Apnea (especially in preterm newborns)

In infants and older children, common seizure mimics include:

- Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES)

- Jitteriness

- Sandifer syndrome (GERD)

- Breath-holding spells

- Movement disorders (Tics, chorea, paroxysmal dyskinesias, etc.)

- Benign sleep myoclonus

- Opsoclonus myoclonus syndrome

- Migraine variants

- Parasomnias

- Syncope (vasovagal or cardiac)

- Self-gratification

- Hypnic jerks

- Hypertonicity in a patient with CP or anoxic brain injury

- Cataplexy

61.10 References

Fisher, R.S., van Emde Boas, W., Blume, W., Elger, C., Genton, P., Lee, P., Engel, J., 2005. Epileptic seizures and epilepsy: definitions proposed by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) and the International Bureau for Epilepsy (IBE). Epilepsia 46, 470–472.

Fisher, R.S., Cross, J.H., French, J.A., Higurashi, N., Hirsch, E., Jansen, F.E., Lagae, L., Moshé, S.L., Peltola, J., Roulet Perez, E., Scheffer, I.E., Zuberi, S.M., 2017, Operational classification of seizure types by the International League Against Epilepsy: Position Paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia 58(4), 522- 530.

Fisher, R.S., Acevedo, C., Arzimanoglou, A., Bogacz, A., Cross, J.H., Elger, J.H., Engel, J. Jr., Forsgren, L., French, J.A., Glynn, M., Hesdorffer, D.C., Lee, B.I., Mathern, G.W., Moshé, S.L., Perucca, E., Scheffer, I.E., Tomson, T., Watanabe, M., Wiebe, S., 2014. ILAE official report: a practical clinical definition of epilepsy. Epilepsia 55(4), 475-82

Newton, RW and Giles, A. Neurological Disorders. In: Lissauer and Carroll (ed). Illustrated textbook of Paediatrics, 5th edition. Elsevier. 2018: 501-24