60 Cerebral Palsy

60.1 Introduction

60.1.1 Definition

Cerebral palsy describes a group of permanent disorders of movement and/or posture resulting from non-progressive (static) disturbances (insult/injury) to the developing foetal or infant brain.

Although the injury is non-progressive (static), the neurological manifestations evolve.

Disturbances of sensation, perception, cognition, communication, and behaviour, by epilepsy, and by secondary musculoskeletal problems, often accompany the motor disorders of cerebral palsy. Cerebral palsy was first described by Dr William Little in 1860. It is also known as Little’s disease, cerebral paralysis, or static encephalopathy. It is usually evident by the time a child is 2 years old. The incidence is approximately 2.2 per 1,000 live births in well-resourced countries. The incidence is higher in lower- and middle-income countries (LMIC). Cerebral palsy is the most common cause of physical disability in children. It is associated with multiple comorbidities.

60.1.2 Classification of cerebral palsy

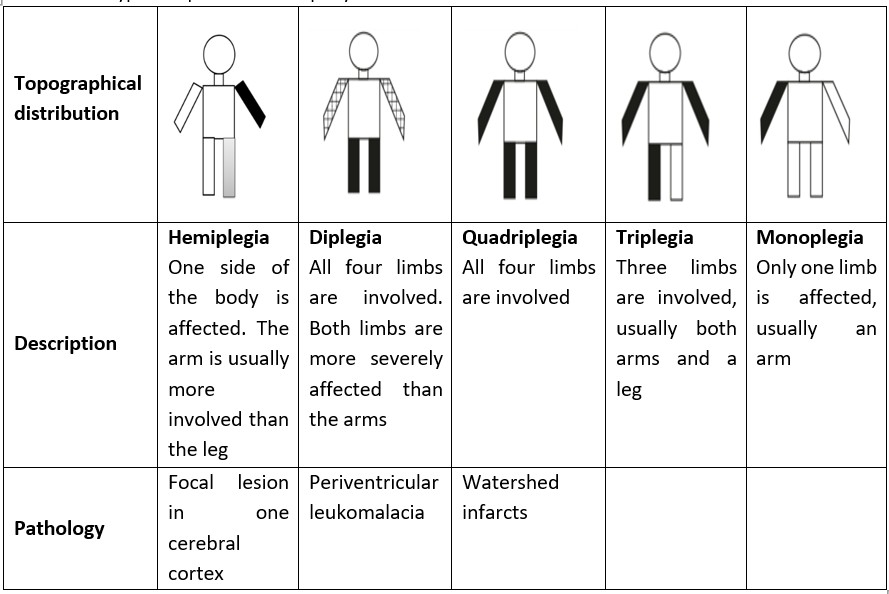

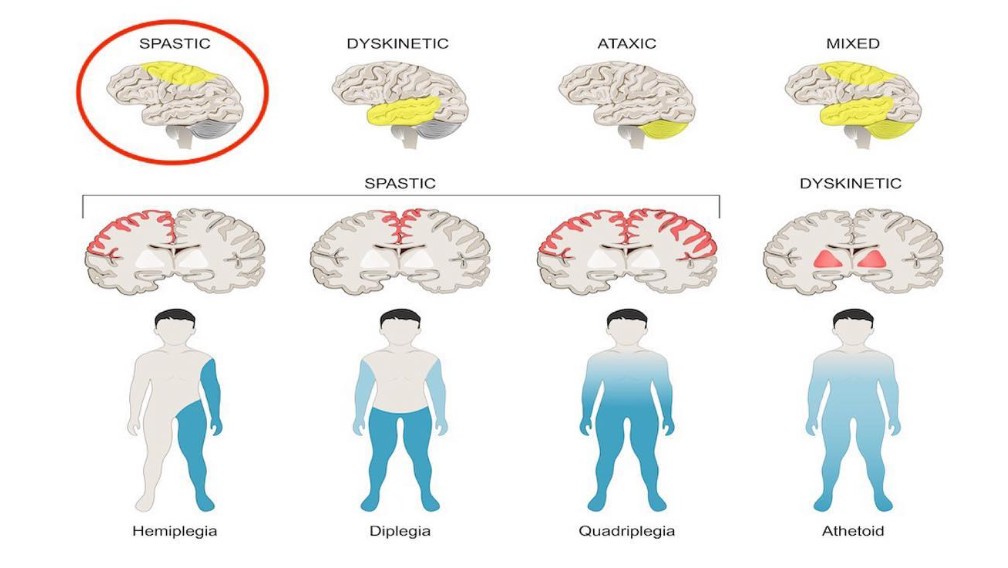

Cerebral palsy is traditionally classified based on the nature of the motor disorder (tone abnormality) and its topographical distribution. Using the motor disorder classification, cerebral palsy is categorized as spastic (pyramidal), dyskinetic (extrapyramidal or athetoid), ataxic, hypotonic, or mixed. Using the topographic distribution, cerebral palsy is classified as quadriplegia, diplegia, hemiplegia, triplegia, and monoplegia.

Recent classifications of cerebral palsy describe the functional assessment of motor abilities using an objective scale. Examples include:

- Gross Motor Functional Classification Scale (GMFCS) for gross motor function

- Manual Ability Classification System (MACS) for upper limb function

- Communication Functional Classification System (CFCS) for communication

- Eating and Drinking Ability Classification System (EDACS) for eating and Drinking

60.1.3 Aetiology and Risk Factors

The risk factors and aetiologies of CP can be grouped based on the timing of the insult as genetic, preconceptional, prenatal, perinatal, or postnatal.

Genetic causes/risk factors include

- Chromosomal syndromes

- Single gene or microdeletion syndromes

Preconceptional risk factors include:

- Maternal illness—seizures, intellectual disability, thyroid disease, iodine deficiency

- Maternal history of stillbirth or neonatal death

- Maternal age over 40

- Low socio-economic status

Prenatal risk factors

- Intrauterine infections (TORCHES)

- Placental abnormalities

- Bleeding in the second or third trimesters

- Eclampsia/pre-eclampsia

Chorioamnionitis

- Maternal drug use, e.g., alcohol, cocaine, cigarette

- Oligo/polyhydramnios

- Intrauterine growth restriction

- Multiple pregnancy

Perinatal risk factors

- Foetal distress

- Difficult deliveries

- Breech delivery

- Prolonged labour

- Instrumental deliveries incl. emergency caesarean section

- Meconium aspiration

- Birth asphyxia à Hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy

- Birth injuries affecting the brain

Postnatal risk factors

- Prematurity

- Low birth weight

- Respiratory distress syndrome

- Hypoglycaemia

- Kernicterus à bilirubin-induced neurological dysfunction

- Neonatal seizures

- Infections, e.g., meningitis, encephalitis

- Trauma à head injuries

- Child abuse, e.g., shaken baby syndrome

- Strokes

- Submersion injuries

60.2 Types of cerebral palsy

60.2.1 Spastic Cerebral Palsy

This is the most common form of CP, accounting for about 70% of cases. It results from injury to the corticospinal (pyramidal) tract or the motor cortex. The features are usually not present at birth, but develop within the first 2 years of life, and include:

- Delayed motor milestones

- Hypertonia (spasticity)

- Hyperreflexia

- Seizures

- Intellectual/learning disability

Spastic CP is further classified based on the anatomical distribution as:

- Monoplegia

- Diplegia

- Hemiplegia

- Triplegia

- Quadriplegia

60.2.1.1 Spastic hemiplegia

This is when the weakness is on one side of the body. On the affected side, the upper limb is usually more severely affected than the lower limb. It results from focal pathology in the cerebral cortex, often due to cerebral malformations or vascular causes such as intrauterine haemorrhage.

Early manifestations of spastic hemiplegia include:

- Fisting on the affected side

- Early handedness (lateralization before 1 year of age)

- Delayed sitting (falls over as affected leg hyper-extends)

- The child does not bear weight on the affected side when held upright

- May not be recognized until 5-6 months of age or later

Late manifestations of spastic hemiplegia include:

- Spastic hemiplegic CP is the most ambulatory form of CP. They typically walk independently by the age of 3.

- Tiptoe walking in the affected foot

- Hemiplegic gait/hemiparesis

- Seizures may occur in 50-60% of patients, usually in the first 2 years of life.

- Intelligence may not be affected

60.2.1.2 Spastic diplegia

This affects all four limbs, but the lower limbs are severely affected, leaving the upper limbs relatively spared. Common etiologic or risk factors are prematurity and hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy in the preterm infant. The pathological finding in the brain is periventricular leukomalacia.

Early manifestations in infants with spastic diplegia:

- They are usually alert and have good socialization

- Their hands open (no fisting)

- They have a normal tone (or even hypotonia) during the first 4 months

- Delayed motor milestones (They delay in sitting and often extend their legs when pulled to sit).

Late manifestations of spastic diplegia:

- They later develop increased tone in the lower limbs (especially in the hip adductors, hamstrings, and gastrocnemius)

- Also, increased deep tendon reflexes, clonus, and Babinski sign in the lower limbs.

- Commando crawling, bottom shuffling, or rolling movement

- Scissoring gait and tiptoeing when pulled to stand

- Delayed walking

- Hip subluxation in children with severe lower limb spasticity

- Usually normal intelligence

- Usually no seizures

60.2.1.3 Spastic quadriplegia

In this type of cerebral palsy, all four limbs are affected. It also affects the face, neck, and trunk. It is caused by diffuse brain injury, such as:

- Hypoxic-ischemic damage in a term infant

- Intrauterine disease

- Cerebral malformations

The typical pathological findings are watershed infarcts.

Early manifestations of spastic quadriplegic cerebral palsy are

- Poor socialization

- Poor neck control

- Infantile reflexes (Moro and tonic-neck) are obligatory, stereotyped, and persist after age 6 months

- The patient may be hypotonic in infancy and later evolve into spasticity.

- Cortical fisting in both hands

Late manifestations of spastic quadriplegia include:

- Severe to profound global developmental

- Microcephaly

- Seizures are common

- Severe intellectual disability

- Diffused increased tone

- Increased deep tendon reflexes, clonus, Babinski sign

- Supranuclear bulbar palsy (dysphagia, dysarthria) presenting as drooling and recurrent aspirations.

- They may never walk or sit alone

- They tend to have cortical visual impairment, disturbances in ocular motility, and hearing impairment.

Less common forms of spastic cerebral palsy are spastic triplegia and spastic monoplegia.

Figure 60.1 summarises the types of spastic cerebral palsy.

60.2.2 Dyskinetic cerebral palsy

This is also called extrapyramidal/choreoathetoid cerebral palsy. Common aetiologies for this form of cerebral palsy include kernicterus and sudden hypoxic-ischaemic episodes, as in uterine rupture or placenta abruptio. The brain pathology shows damage in the extrapyramidal system and the basal ganglia.

Early manifestations of dyskinetic cerebral palsy include:

- No choreoathetosis in the first 2 years of life

- Often hypotonic, but sometimes presents with fluctuating muscle tone

- Delayed motor milestones

- Poor neck control

- Sensorineural deafness

- Normal socialization

Late manifestations include:

- Movement disorders: Choreoathetosis, dystonia

- Symmetrical distribution

- Dental enamel dysplasia

- Difficulty with speech (dysarthria)

- Swallowing difficulty leading to drooling

- Affected children may or may not walk independently

- Intelligence can be normal

- Seizures are not common

60.2.3 Ataxic cerebral palsy

This results from damage to the cerebellum. Patients experience problems with balance and deep perception, presenting with an unsteady gait and difficulty with movement that requires a lot of control, such as writing. Their muscle tone may be increased or decreased.

60.2.4 Mixed cerebral palsy

Patients with mixed cerebral palsy have more than one type of cerebral palsy, usually a mixture of spasticity and athetoid movements, with tight muscle tone and involuntary reflexes. In mixed CP, different parts of the brain are affected. Figure 60.2 shows the topographical and physiologic classification of cerebral palsy.

60.3 Comorbidities of cerebral palsy

These are conditions that occur with greater frequency in children with cerebral palsy than in the general population. They include:

- Developmental delays

- Seizures

- Ophthalmologic/visual abnormalities including Cortical visual impairment, Disorders of ocular motility, Refractive errors, and Optic atrophy

- Hearing impairment

- Speech defects, including delayed speech, poor articulation, loss of voice modulation

- Learning/intellectual disability

- Feeding problems/swallowing difficulties

- Aspiration pneumonia

- Gastroesophageal reflux

- Gait abnormalities

- Contractures

- Hip subluxation

- Failure to thrive/neglect/abuse

- Behavioural and emotional problems such as ADHD, depression, and ASD

60.4 Diagnosis

The diagnosis of CP is clinical. It is based on the constellation of symptoms and signs in the affected child. Special investigations have a limited role in confirming the diagnosis but may contribute to determining the aetiology and the timing of the insult. Investigations may also help to exclude differential diagnoses and to identify comorbidities.

Investigations that may be employed include various modalities of neuroimaging, such as transcranial USG, brain CT scan, and brain MRI

Transcranial ultrasound: This is useful in the neonate up to 6 months, for the detection of large structural abnormalities

Brain CT Scan/MRI: These give a better definition of structures. The CT is used in children >1 year old due to the risk associated with radiation in younger children, while the MRI is helpful at any age. However, the MRI is more challenging to perform due to its limited availability, high cost, and the prolonged sedation required.

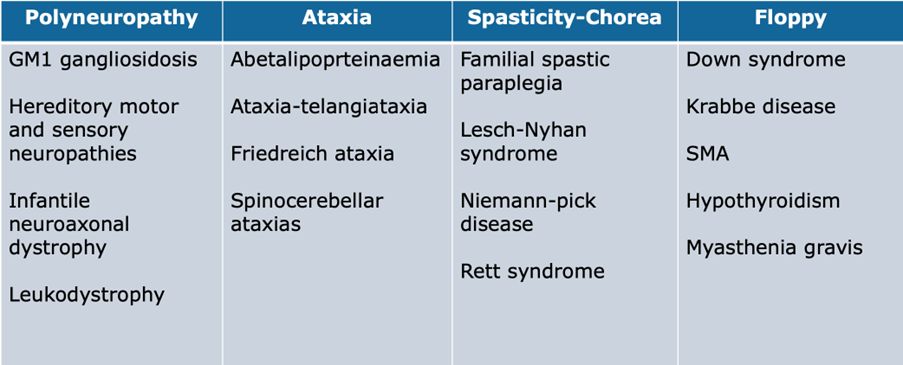

60.5 Features that suggest a progressive CNS disorder rather than CP

- Abnormally increasing head circumference: think hydrocephalus, tumour, leukodystrophies

- Eye abnormalities such as cataract, retinal pigmentary degeneration, optic atrophy: think neurodegenerative disease

- Skin abnormalities such as hypopigmentation, café-au-lait spots, nevus flammeus, etc: think neurocutaneous disorders, e.g., Sturge-Weber syndrome, neurofibromatosis, etc.

- Hepatomegaly with or without splenomegaly: think storage disease

- Sensory abnormalities: think peripheral nerve disorders.

Figure 60.3 lists a few examples of disorders that are sometimes misdiagnosed as cerebral palsy

60.6 Management of the child with cerebral palsy

In the management of the child with cerebral palsy, the main goals of treatment should be to help the child reach their full potential by:

- Maximizing mobility through physical therapy

- Providing physical support using aids such as splints, walkers, and wheelchairs

- Speech and occupational therapy

- Surgery to correct abnormalities, improve mobility, and reduce spasticity

- Special educational services

It is essential to adopt a multidisciplinary approach in the management of .the child with cerebral palsy. In contrast, the child remains under the care of one paediatrician, usually a developmental paediatrician.

The role of the multidisciplinary team (MDT) members in the management of cerebral palsy includes:

- Developmental paediatrician – monitors a child’s development and coordinates multidisciplinary care for the patient.

- Neurologist – management of neurological disorders, including seizures and movement disorders.

- Audiologist – hearing assessment

- Speech therapist –assessment of speech and swallowing

- Ophthalmologist – visual defects

- Nutritionist/Dietician – growth failure, nutritional deficiencies

- Specialist teachers

- Physiotherapist – addressing spasticity, posture, and gait abnormalities, among others.

- Orthopaedic surgeon – structural deformities, contractures, scoliosis.

- Neurosurgeon – surgical management of spasticity and scoliosis.

- Occupational therapist – difficulties with fine movements and activities of daily living (ADLs)

- Clinical psychologist

- Social/community worker

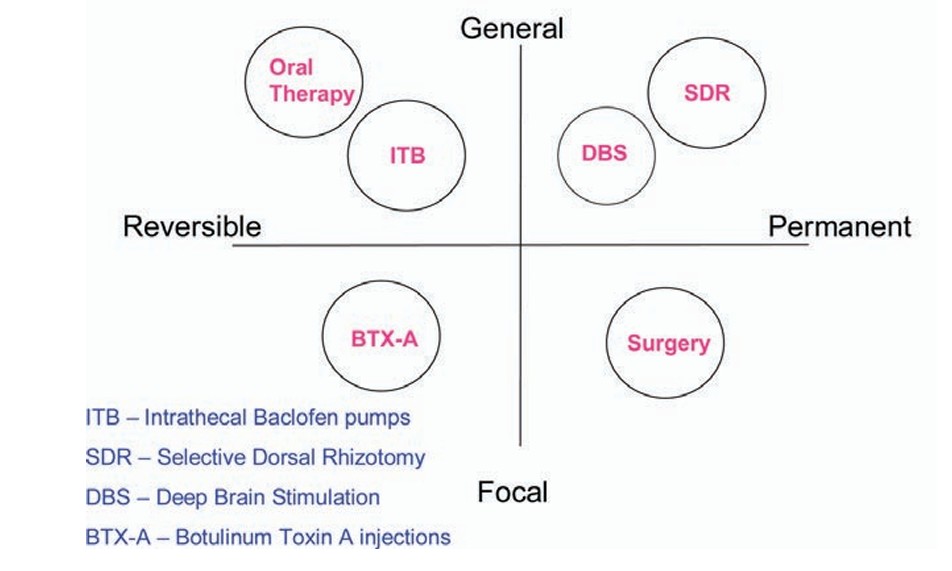

60.6.1 Management of spasticity

Spasticity may be focal or generalised, and treatment modalities are either reversible or permanent. For generalised spasticity, some reversible modalities used are oral therapy (baclofen, diazepam, etc.) and intrathecal baclofen pumps. Permanent modalities for generalised spasticity include deep brain stimulation and selective dorsal rhizotomy.

For focal spasticity, botulinum toxin A injection provides reversible relief, whereas focal surgeries, such as tendon release, provide permanent relief.

These are summarised in Figure 60.5 below.

60.7 Preventive strategies for cerebral palsy

- Antenatal measures

- Use of magnesium sulphate for neuroprotection

- Use of antenatal corticosteroids in anticipated preterm deliveries

- Tocolysis

- Measures to prevent preterm births

- Appropriate antibiotic use in PROM

- Vaccination against rubella and congenital infections

- Regular ANC check-ups

- Avoid alcohol, tobacco, and drugs

- Maintaining a healthy lifestyle for the mother

- Perinatal/neonatal care

- Early detection and management of neonatal care

- Neuroprotection with moderate hypothermia for newborns with HIE

- Avoidance of unnecessary oxygen supplementation

- Early detection and treatment of neonatal hypoglycaemia

- Postnatal and childhood care

- Measures to prevent head injury, including the use of baby care seats, the prevention of falls, and shaking.

- Genetic screening and counselling for families with cerebral palsy

60.8 Current innovations in the management of cerebral palsy

Systemic hypothermia: Controlled medical cooling of the body’s core temperature may protect the brain and decrease the rate of death and disability from brain injuries. Hypothermia is effective in treating neurologic symptoms in babies with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE)

Stem cell therapy is being investigated as a potential treatment for cerebral palsy. Stem cells are capable of differentiating into various cell types within the body. Scientists are hopeful that stem cells may be able to repair damaged nerves and brain tissues. Clinical studies are examining the safety and tolerability of umbilical cord blood stem cell infusion in children with cerebral palsy.

60.9 Prognosis

Cerebral palsy is not a progressive condition, and so living into old age is possible. Regression or worsening of long-term symptoms is not characteristic. Prognosis varies according to the severity of the disorder. The lifespan of patients with cerebral palsy is usually reduced by complications such as reduced mobility, feeding difficulties, respiratory infections, and epilepsy. In the US, the average life span of patients with cerebral palsy was reported as 35 years in 2008.