49 Hypertension

49.1 Introduction

Blood pressure is the force exerted by the blood against any unit area of the vessel wall. Physiologically, \[BP = CO \times TPR = SV \times HR \times TPR\] Where:

- \(HR\) is the Heart Rate

- \(BP\) is the Blood Pressure

- \(TPR\) is the Total Peripheral Resistance

- \(CO\) is the Cardiac Output

- \(SV\) is the stroke volume

49.2 Ways of measuring blood pressure

- Direct intra-arterial measurements by placing a catheter into the vessel and measuring the pressure “in line” with the vessel (end-on-pressure). This method is used by physiologists and Intensivists. The principle is employed in the measurements of central venous pressure and intracranial pressure in clinical practice.

- The auscultatory method is done with the use of a sphygmomanometer (either mercury or aneroid) and a stethoscope. This is the gold standard in clinical practice. Korotkoff sounds 1 and 5 sounds are measured for systolic and diastolic bleed pressures respectively. Values obtained are generally lower than direct & oscillometric measurements.

- The palpation method (flush technique) is performed with the use of a sphygmomanometer and palpating finger. Largely unreliable. Only systolic blood pressure can be measured with this technique. The palpated pulse is generally lower than Korotkoff sound 1 by 10mmHg.

- The oscillometric method uses a sphygmomanometer and a monitor e.g. digital blood pressure devices and Dynamap. Here, pulsatile blood flow through arterial wall oscillations is transmitted to the cuff encircling the extremity. Korotkoff sound 1 is recorded at the point of rapid increase in oscillation amplitude. Korotkoff sound 5 is recorded as the point of a sudden decrease in oscillation amplitude. Values obtained by oscillometric measurements are generally higher than auscultatory.

- Doppler ultrasound technique: Here a Doppler ultrasound is held over the pulse to magnify the sound so that it is audible without a stethoscope. The sound detected may be 5mmHg higher than Korotkoff sound 1.

- Ambulatory blood pressure measurements. Here, multiple measurements are recorded over time (e.g. 24 hours) with digital devices attached to the limb whilst the patient engages in normal activities outside the hospital. Results are analysed on a computer or paper tracer built into the device using the mean of the readings. It provides a truer picture of blood pressure trends useful in diagnosing “white coat hypertension” and nocturnal hypertension (absence of a normal physiological drop in blood pressure during sleep).

49.3 Definition of Hypertension in children

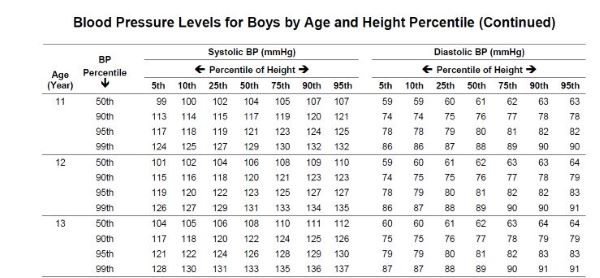

In adults, the epidemiological definition is based on the risk of adverse events (e.g. Stroke) being>140/90mmHg. In children, hypertension is defined statistically based on normative data: ≥ 95th centile for age, height, and gender (Refer to height centile chart and blood pressure levels). By this statistical definition, 5% of children will be classified as hypertensives. Other definitions include:

Normal blood pressure: < 90th centile for age, height, and sex.

Pre-Hypertension: 90th – <95th centile for age, height, and sex

Stage 1 Hypertension: 95th - 99th + 5 mmHg

Stage 2 Hypertension: > 99th centile + 5mmHg

A sample of the blood pressure chart is shown below.

49.4 Plotting the blood pressure centile

- Measure the child’s height.

- Determine the height centile. If the height centile falls between 2 centiles, use the closest centile. Otherwise, use the lower height centile.

- Determine the blood pressure centile.

- Classify blood pressure using the definitions above.

49.5 Hypertensive emergency

This is an acutely elevated blood pressure with evidence of threatening end-organ damage involving the following organs:

- Brain (severe headache, visual changes, cranial nerve palsy, papilloedema)

- Heart (acute chest pain and tightness, shortness of breath)

- Kidney (decreased urine output acutely, proteinuria and haematuria on dipstick)

It is thus a symptomatic, severe Hypertension.

49.6 Hypertensive Urgency

This is severe hypertension without evidence of end-organ damage or symptoms. The blood pressure should nevertheless be treated urgently but not aggressively like in a hypertensive emergency to prevent progression into a hypertensive emergency. If possible, the patient should be managed as in-patient.

49.7 Rules of blood pressure measurement

- Select the right cuff size.

- The length of the inflation bladder should be at least 80% of the mid-arm circumference.

- The width of the inflation bladder is at least 40th of the mid-arm circumference.

- The child should rest for at least 5 minutes in a comfortable environment and position.

- Arm resting and supported at heart level (The reference level. Values outside this reference level are higher). The lower edge of the cuff is 2cm above the cubital fossa.

- Bladder tubings should lie over the brachial artery.

- The Bell of the stethoscope is used.

- Korotkoff sounds 1 and 5 are used for systolic and diastolic respectively.

- Multiple measurements are made (preferably at different settings) and the lowest reading is taken. For research purposes, 3 measurements are taken and an average of the last 2 used.

Blood pressure readings obtained in the legs are 10-20mmHg higher than the arm pressure in any individual. Arm blood pressure higher than leg blood pressure occurs in aortic coarctation distal to ductus arteriosus.

49.8 When to suspect hypertension

Suspect hypertension in any child with any of the following conditions:

- Alteration in consciousness including aggressive behavior and convulsion

- Oedematous

- Known kidney disease or evidence of abnormal urinalysis

- Heart failure

- Obesity

- Failure to thrive

- Stroke or other palsies including cranial nerve palsy

- History of Low Birth Weight (small number of nephrons)

- Unexplained anaemia, or blurred vision

- Neurofibromatosis

- Other syndromes like Turner & Williams

49.9 Aetiology of hypertension

Generally, childhood Hypertension is considered to be of secondary cause until proven otherwise. This is particularly so among the very young and the severely hypertensive. The majority (~80%) are of renal origin. However, the number of children with essential Hypertension is on the rise, particularly among obese adolescents and those with a positive family history.

Broadly, aetiology can be categorized into:

- Renal disease

- Vascular disorders

- Endocrine causes

- Neurologic causes

- Renal tumours

- Catecholamine-secreting tumours

- Drug-induced

- Miscellaneous causes

However, since these are often age-specific categorizations are done by age as below:

49.9.1 Neonate to one-year

Congenital

- Congenital lesions of the vasculature

- Renal Artery Stenosis

- Aortic coarctation

- Congenital lesions of renal parenchyma

- Polycystic Kidney disease

- Dysplastic kidneys

- Obstructive uropathy

- Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia

- 11-β hydroxylase deficiency

- 17-αhydroxylase def

Acquired

- Renal artery or vein thrombosis secondary to umbilical artery or vein catheterisation

- Bronchopulmonary dysplasia

- Medications

- Theophylline/caffeine

- Phenylephrine and Ephedrine Nasal Drops in cold medications

- Steroids

- Vitamin D intoxication

- Total Parental Nutrition (high Ca2+)

- Maternal drug use: Cocaine, heroin

49.9.2 One- to five years

- Renal Artery Stenosis

- Glomerulonephritis

- Renal vein thrombosis

- Wilms tumour

- Neuroblastoma

- Phaeochromocytoma

- Cystic kidney disease

- Monogenic Hypertension (e.g. Liddle’s syndrome)

49.9.3 Five- to ten-years

- Glomerulonephritis

- Renal scars from reflux nephropathies or Urinary Tract Infections

- Renal Artery Stenosis

- Cystic renal disease

- Endocrine tumours

- Essential Hypertension

- Obesity

49.9.4 Ten- to twenty-years

- Obesity

- Essential hypertension

- Reflux nephropathies with repeated Urinary Tract Infections

- Glomerulonephritis

- Renal Artery Stenosis

- Endocrine tumours

- Hyperthyroidism

- Drugs (Oral Contraceptive Pill, illicit drugs)

49.10 Evaluation of the Hypertensive Child

- Patient’s history

- Symptoms of renal disease (haematuria, oliguria, evidence of bodily swelling, polyuria, enuresis)

- Symptoms of vasculitis or rheumatology ( Joint swelling & rash)

- Past medical history (umbilical artery/vein catheterisation, previous renal disease e.g. Previous swelling)

- Drug History (steroids, Oral Contraceptive Pill, amphetamines, other illicit drugs)

- Birth History: Low Birth Weight

- Family History of Hypertension

Clues on physical examination include:

- Coarctation of the Aorta & Takayasu:

- Femoral artery delay or imperceptible

- Blood pressure discrepancy between arm & leg →COA, Takayasu arteritis

- Neurofibromatosis

- Cafѐ au lait spots

- RAS, Takayasu arteritis

- Abdominal bruit

- Congenital adrenal hyperplasia

- Ambiguous genitalia

- Dysmorphism suggestive of Turner or William syndromes

- Signs of Chronic Renal Failure: Growth failure (stunted), renal rickets, anaemia, oedema

- Bedside urine dipstick positive for protein and blood (± oedema)

49.11 Investigations

The rationale is 2-fold:

- To define aetiology

- To assess the presence of end-organ damage

Some of the investigations include:

- Full blood count

- Urine dipstick, microscopy and culture

- BUE, Serum Creatinine, Ca, Mg, PO4, blood gases

- Uric acid

- KUB ultrasound and Doppler studies to rule out Renal Artery Stenosis

- Chest X-ray for cardiomegaly

- Echocardiogram for Left Ventricular Hypertrophy (end organ damage)

- Fundoscopy

- Plasma Renin Activity (PRA) for RAS & renin secreting tumours

- Pre/post captopril nuclear scan

- MRA or CT Angiogram

- DMSA scan for renal scars

- Urine HVA & VMA for catechol amine secreting tumours/MIBG scintigraphy

49.12 Uric Acid and hypertension

Uric acid is increasingly being implicated in the pathogenesis of Hypertension in both adults and children. It is believed to cause endothelial dysfunction leading to microvascular and inflammatory injury to the kidneys. There are also reduced levels of endothelial-derived nitric oxide and associated elevation of the Renin-Aldosterone-Angiotensin System. Elevated uric acid levels in hypertensive individuals are associated with adverse outcomes like stroke. Allopurinol treatment is advocated for such individuals.

49.13 Complication of Hypertension

Some complications of Hypertension are listed below:

- Hypertensive encephalopathy

- Left Ventricular Failure

- Stroke

- Subarachnoid haemorrhage

- Secondary renal damage

- Retinopathy

49.14 Treatment of hypertension

49.14.1 Non-drug treatment

- Reducing salt intake

- Weight reduction for obesity-related hypertension

- Intake of more vegetables on account of potassium richness

49.14.2 Drug Treatment

Principles of anti-hypertensive therapy:

- Long-acting (once-daily medication)

- Maximise treatment dosage before adding on

- Agents used will come from the “ABCD” group:

- ACE inhibitor and ARBs (Avoid if RAS suspected or in hypovolaemia)

- Beta-blocker

- Calcium channel blocker

- Diuretic

- Every other drug (methyl dopa, alpha-blockers, vasodilators like hydralazine

Generally, A & B drugs are not combined for Blood pressure control. Rather: A + C + D or B + C + D

49.15 Hypertensive encephalopathy

Hypertension with changes in mental status and/or seizures. Other manifestations are:

- Facial palsy

- Visual changes→blindness

- Coma

Pathophysiology: Disruption of the normal autoregulatory mechanisms of cerebral blood flow. The inability of cerebral vasculature to constrict appropriately in response to the abrupt increase in cerebral blood flow leads to cerebral hyperperfusion. Generally, short-acting antihypertensives are preferred in the initial instance of treatment so that any potentially harmful drop in blood pressure (which could lead to Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome {PRES}) could be reversed. Subsequently, long-acting agents could be used Sublingual nifedipine could cause a precipitous drop in blood pressure so it is best avoided or should be used with extreme caution.

Treatment outline:

- Use anti-hypertensive drugs

- Blood pressure should be brought down slowly to a desirable level (?stage I) by 48hrs (though not to normal levels) as follows:

- 1/3 of total blood pressure reduction in 1st 12-hrs

- Next one-third of the subsequent 12-hrs

- Final one-third over 24-hrs

- Alternatively, by a quarter within 6 hours, and the rest in the next 24-36hrs

Commonly preferred drugs include Labetalol infusion, Na nitroprusside infusion, and IV hydralazine infusion. After achieving the desired blood pressure target, oral antihypertensives are then started.