22 Atrial Septal Defect

22.1 Introduction

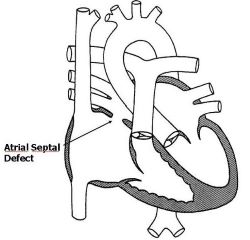

An Atrial Septal Defect (ASD) is a defect in the wall separating the left and right atria.

22.2 Incidence/Prevalence

It is the second most common congenital heart disease and may occur in as much as 25% of all congenital heart disease patients. It is thought to have a small female preponderance. Still, in a compilation of all electrocardiogram cases in Kumasi, it formed 26% of the patients and showed no difference in incidence between sexes. There are four main types: Secundum ASD (50-70%), Primum ASD (~30%), Sinus Venosus ASD and Coronary sinus ASD. Figure 22.1

22.3 Aetiology

Most ASDs are thought to occur sporadically, but there are recorded associations with some genetic defects and syndromes. (Caputo et al. 2005) Among these are Holt-Oram, Noonan, Down, and Budd-Chiari syndrome.

22.4 Pathophysiology

Since the pressure in the left atrium is higher than that of the right, the high oxygen-content blood shunts from the left atrium to the low oxygen-content right atrium. Thus an uncomplicated ASD is acyanotic. The shunting also leads to volume overload of the right atrium, right ventricle, pulmonary artery and lungs. This consequently results in dilatation of the right atrium, right ventricle and pulmonary artery, and pulmonary oedema. The low pressure in the atria implies low pressure in the right ventricle, pulmonary artery and lungs. This reduces the extent of pulmonary oedema and, subsequently, overt heart failure in a child with ASD, compared to other congenital heart defects such as ventricular septal defects. However, longstanding long-standing lesions or relatively large ones, especially those with a pulmonary-to-systemic flow ratio of 2 or more, could lead to heart failure and pulmonary hypertension after about 15 to 20 years with subsequent reversal of the shunt.

22.5 Signs and symptoms

Most children with an atrial septal defect are without overt symptoms. However, those with relatively large defects with a high Qp:Qs may result in heart failure. Therefore, many of these patients have been diagnosed incidentally when they, for instance, report to the health institution for another complaint. They tend to have slender bodies and reduced exercise tolerance.

Auscultation usually reveals a widely fixed-split second heart sound and an ejection systolic murmur of grade 2/3 to 3/6, loudest at the left upper sternal border. Unfortunately, many ASDs are silent as well. These properties lead to many undiagnosed ASD that are subsequently seen in adulthood.

22.6 Investigations

- At the bedside, pulse oximetry would likely reveal a normal SpO2 as this is an acyanotic congenital heart disease.

- A chest X-ray could show cardiomegaly with dilatation of the right side of the heart. Prominence of the pulmonary artery and an increase in vascular markings may also be present.

- The electrocardiogram will likely show a right axis deviation due to the dilated right ventricle and a right atrial enlargement.

- An echocardiogram is diagnostic as it visualises the defect, quantifies the shunt and other chamber sizes, and identifies possible complications.

- Cardiac catheterisation is often done in long-standing cases to detect complications, possibly pulmonary hypertension, and quantify the shunt volume.

22.7 Treatment

Treatment depends on the age at diagnosis and the size of the defect. For a small defect with no signs of heart failure, and in a child less than 3 years, counselling and regular review may be what is required. The echocardiogram should be repeated at 4 years, and surgical or device closure should be considered if the defect persists. For large defects, heart failure medications can be started as planning of immediate surgical closure is being made. Closure of the ASD is by use of a device or, as may occur more often in Ghana, by open heart surgery. There is no need for exercise restriction or prophylaxis for endocarditis.

22.8 Prevention

There is no known mode of prevention of ASDs. However, early and appropriate treatment of the associated symptoms and complications go a long way in improving quality of life.

22.9 Complication

- Many patients with ASDs may not grow appropriately and instead become thin.

- Arrhythmias may arise because of the dilated right atrium.

- Though there are reported cases of paradoxical strokes in patients with ASDs, it remains an uncommon occurrence.

- Infective endocarditis is rare in ASDs.

22.10 Prognosis

Most ASDs will close spontaneously by 4 years, with smaller ones having a higher closure rate than bigger ones. A long-standing large defect, however, leads to chronic heart failure and pulmonary hypertension in early adulthood. Prognosis is generally good, with many living into adulthood, even without corrective surgery. Post-surgical mortality is currently less than 0.5%. The patient will need little long-term follow-up after the corrective surgery.

22.11 Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis includes pulmonary stenosis and a pink Tetralogy of Fallot.