24 Patent Ductus Arteriosus

24.1 Definition

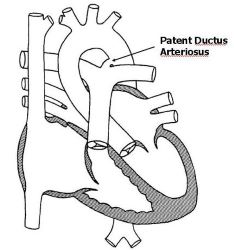

Patent Ductus Arteriosus (PDA) is an acyanotic congenital heart disease. that results from the persistence into the post-natal life of the normal fetal vascular conduit between the pulmonary and systemic arterial systems. Figure 24.1 Normally, the ductus arteriosus functionally closes within the first 1-3 days after birth. Structural closure is usually completed by the 3rd week of birth.

24.2 Incidence/prevalence

PDAs represent about 5-10% of all congenital heart defects, with an equal male-to-female ratio.(Borges-Lujan et al. 2022) It made up 23% of all electrocardiograph diagnoses of heart diseases seen in Kumasi, with a male-female-ratio of 1:0.9. This high proportion of PDAs in this cohort could be because a significant proportion of the children scanned were preterm infants.

24.3 Aetiology

Although there are no recognized etiological factors, PDAs are associated with a few recognisable conditions. These include:

- Prematurity - The more premature a baby is the higher the incidence of PDA. it is seen in as much as 80% of babies born from 24 to 28 weeks.

- Teratogenic agents such as Congenital Rubella, fetal alcohol syndrome, fetal hydantoin syndrome and maternal phenylketonuria

- Genetic or familial factors such as Trisomy 21, Trisomy 18, Trisomy 13, Noonan syndrome, CHARGE association, VATER association, Holt-Oram syndrome, Treacher Collins syndrome, PHACE Syndrome, Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome, Cri du chat syndrome

- Living at high altitudes has long been associated with a higher incidence of PDAs

- Idiopathic - Many patients with a PDA have no identifiable risk factors.

24.4 Pathophysiology

Ductus arteriosus in fetal circulation is indispensable to allow right-to-left shunting of nutrient-rich oxygenated blood from the placenta to the fetal systemic circulation, bypassing the fetal pulmonary circuit. At birth, the rise in PaO2 and decline in prostaglandin concentration cause closure of the ductus arteriosus, typically beginning within the first 10 to 15 hours of life. If this normal process does not occur, the ductus arteriosus will remain patent. The PDA then results in excess blood shunting from the aorta, across the duct and into the pulmonary artery. This shunting causes volume overload. There is therefore a circuit of excess blood volume in the pulmonary arteries, lungs, left atrium, left ventricle, and aorta. This subsequently leads to dilatation of the left pulmonary artery, left atrium and left ventricle as well as pulmonary edema and heart failure.

24.5 Signs and symptoms

Symptoms vary based on the volume of additional blood flow to the lungs.

- The degree of the shunt depends on:

- The size of the PDA (including diameter, length, and tortuosity). Bigger ducts with shorter lengths often result in worse symptoms. Conversely, patients with small PDAs are often asymptomatic.

- Pulmonary vascular resistance when high does not encourage shunting across the duct. However, as the resistance drops the shunt gets worse, with worsening symptoms.

- Moderate to larger shunts produce the symptoms of congestive heart failure as the pulmonary vascular resistance decreases over the first 6 to 8 weeks of life.

- The physical examination depends on the size of the shunt, and to a lesser extent the age and maturity of the patient.

Premature infants may present with:

- Tachypnoea, crackles, tachycardia

- Hyperdynamic precordium and bounding pulses with wide pulse pressure

- Pansystolic murmur loudest at the left upper or mid-sternal border.

- With a large PDA and equalization of pressure between the main pulmonary artery and the aorta, no murmur may be heard.

- Soft tender hepatomegaly

Infants and older children with small PDAs may present with:

- A pansystolic murmur loudest in the 2nd left intercostal space

- Murmur becomes continuous as the pulmonary vascular resistance decreases over the first months of life.

Infants and older children with moderate to large PDA may present with:

- Louder murmur with a harsh quality and acquires a machine-like quality often being heard posteriorly. A systolic thrill may be felt at the left upper sternal border.

- Tachycardia, bounding pulses with a wide pulse pressure, and a mid-diastolic low-frequency rumbling murmur may be audible at the apex with a large PDA

- With severe left ventricular failure the classic PDA signs may disappear, but there will be findings consistent with congestive heart failure (tachycardia, S3 gallop at the apex, tachypnoea, soft tender hepatomegaly, bi-basal crackles)

- Pulmonary hypertension may occur in long-standing cases. In advanced cases of irreversible pulmonary vascular disease, cyanosis occurs with the reversal of shunting.

24.6 Investigations

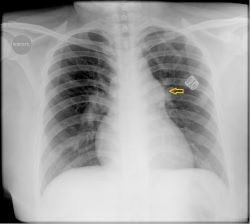

- Chest X-ray: Varies from normal (small PDAs) to prominence of main and peripheral pulmonary arteries and vasculature. Findings are more pronounced with moderate to large PDAs and may show cardiomegaly, and increased pulmonary vascular markings proportional to the left-to-right shunt. A dilated pulmonary artery may be seen on the chest x-ray in long-standing cases. Figure 24.2 Pulmonary oedema can be seen with congestive heart failure.

- Electrocardiogram: Findings vary from normal (small PDAs) to evidence of left atrial dilatation and left ventricular hypertrophy with moderate to large PDA. Evidence of bi-ventricular hypertrophy in long-standing cases. If pulmonary hypertension is present, evidence of right ventricular hypertrophy may be seen.

- Echocardiogram: This delineates the PDA and assesses the size of the left atrium and ventricle. Useful for evaluating pulmonary hypertension. Doppler for determining the flow pattern.

- Cardiac catheterisation: most often not essential for diagnosis. Can be performed for treatment using transcatheter closure techniques

24.7 Treatment

- Supportive treatment including careful use of oxygen and respiratory assistance

- Management of CHF with diuretics commonly furosemide and spironolactone, digoxin and afterload reduction on a case-by-case basis

- Pharmacologic closure of PDA: Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) such as indomethacin or ibuprofen; are not usually effective in infants or older children but are in the early neonatal period. Contraindications to pharmacologic closure include co-existing congenital heart defects that are duct-dependent, renal impairment, thrombocytopenia and associated conditions such as NEC and IVH.

- Surgical closure is indicated in symptomatic or haemodynamically significant PDA. Surgical closure is achieved by open surgical ligation and division, video-assisted thoracoscopic ligation or transcatheter occlusion with coils or other devices.

24.8 Complications

The recognised complication of PDA includes infectious endocarditis, pulmonary hypertension and heart failure.

24.9 Prognosis

- The chance of spontaneous closure in a preterm baby is about 95%, while the likelihood of spontaneous closure in a term baby is more than 90% by age 1.(Yuan et al. 2021) This is because PDA in term infants results from a structural abnormality of the ductal smooth muscles rather than a decrease in responsiveness of the ductal smooth muscles to oxygen.

- Heart failure and risk of recurrent chest infections develop for large shunts

- Large shunts are also a risk for the development of pulmonary hypertension

- Surgical treatment now has an almost 100% success rate in many centres.

24.10 Differential diagnosis

Other acyanotic congenital heart diseases are possible differentials. These include a large atrial septal defect and a coarctation of the aorta.