25 Coarctation of the Aorta

25.1 Definition

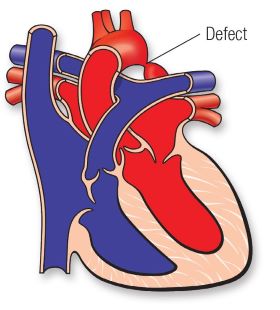

Coarctation of the aorta (CoA) is a congenital heart defect characterized by the narrowing of the aorta, the major artery responsible for carrying oxygen-rich blood from the heart to the rest of the body. This condition accounts for approximately 5-8% of all congenital heart defects in children and is more prevalent in males than females. CoA can present with varying degrees of severity and may occur as an isolated defect or associated with other cardiac anomalies, such as bicuspid aortic valve, ventricular septal defect (VSD), or complex syndromes like Turner syndrome.

25.2 Anatomy and Pathophysiology

The aorta plays a crucial role in distributing oxygenated blood from the heart’s left ventricle to the systemic circulation. In CoA, the narrowing typically occurs at the isthmus of the aorta, which is located distal to the left subclavian artery and near the ductus arteriosus, a fetal blood vessel that normally closes after birth. The severity of CoA depends on the degree of narrowing, which can obstruct blood flow and increase the heart’s afterload.

The left ventricle must work harder in children to pump blood through the narrowed segment, leading to left ventricular hypertrophy. Prolonged obstruction may result in high blood pressure (hypertension) in the upper body and diminished blood flow to the lower body. Collateral circulation often develops as the body compensates using smaller vessels to bypass the narrowing, but this is not always sufficient to normalize blood flow.

25.3 Clinical Presentation

The clinical manifestations of CoA in children vary based on the severity of the narrowing. Severe cases may present in infancy, while milder forms might remain undetected until adolescence or adulthood.

25.3.1 Infants:

Severe CoA may cause critical illness within the first few weeks of life, especially after the ductus arteriosus closes.

Symptoms include poor feeding, failure to thrive, lethargy, respiratory distress, and signs of heart failure.

Pulses in the lower extremities may be weak or absent, and blood pressure measurements reveal significant upper-to-lower extremity discrepancies.

25.3.2 Older Children:

Milder CoA might be asymptomatic or present with less obvious symptoms, such as fatigue, leg pain during exercise (claudication), headaches, or nosebleeds.

Hypertension is common in older children and may be detected incidentally during routine health check-ups.

Physical examination often reveals a systolic murmur heard best over the back, diminished or delayed femoral pulses, and upper extremity hypertension relative to the lower extremities.

25.4 Diagnostic Evaluation

Timely diagnosis of CoA is critical to prevent complications and ensure appropriate management. Several diagnostic tools are employed to confirm the condition and assess its severity.

Physical Examination:

- Blood pressure measurements in all four extremities to identify discrepancies.

- Palpation of pulses to detect reduced or absent femoral pulses.

- Auscultation for murmurs and other abnormal heart sounds.

Imaging Studies:

- Chest X-ray: May show rib notching (caused by collateral vessels) and a characteristic “3 sign” of the aorta.

- Echocardiography: The primary diagnostic tool for visualizing the narrowed segment of the aorta and assessing associated anomalies.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) or Computed Tomography (CT): Provides detailed anatomical information, especially in older children or when planning surgical interventions.

Cardiac Catheterization:

- Invasive procedures are used for definitive diagnosis in certain cases and for interventional treatment.

- Measures pressure gradients across the narrowed segment and evaluates the severity of obstruction.

25.5 Management

The treatment of CoA depends on the child’s age, the severity of the condition, and the presence of associated cardiac defects. The primary goal is to relieve the obstruction, restore normal blood flow, and prevent complications.

Medical Management:

In neonates with severe CoA and ductal-dependent circulation, prostaglandin E1 infusion maintains ductus arteriosus patency and ensures adequate lower body perfusion.

Medications such as inotropes and diuretics may be administered to manage heart failure symptoms before definitive treatment.

Surgical Repair:

Surgical correction is often the preferred treatment for infants and young children with severe CoA.

Techniques include resection of the narrowed segment with end-to-end anastomosis, subclavian flap aortoplasty, or patch augmentation.

Surgery is typically performed during infancy or early childhood to minimize long-term complications and avoid the development of significant collateral circulation.

Catheter-Based Interventions:

Balloon angioplasty and stent placement are minimally invasive alternatives, particularly in older children and adolescents.

These procedures are often used for coarctation after initial surgical repair or in cases where surgery is not feasible

25.6 Complications

Untreated or inadequately treated CoA can lead to significant complications, including:

- Persistent hypertension, even after successful repair.

- Aortic aneurysm or dissection, particularly in cases of long-standing hypertension.

- Heart failure due to left ventricular strain.

- Premature coronary artery disease and cerebrovascular events, such as stroke.

- Infective endocarditis, especially in cases with associated valvular abnormalities.

25.7 Long-Term Outcomes

With advancements in diagnostic techniques and treatment modalities, the prognosis for children with CoA has improved significantly. However, long-term follow-up is essential to monitor for residual or recurrent narrowing, hypertension, and other complications. Lifelong care under a cardiologist familiar with congenital heart defects is recommended.

25.8 Prognosis

The long-term outlook for children with CoA largely depends on the timing and success of treatment. Early intervention typically results in good outcomes, with most children leading normal or near-normal lives. However, ongoing surveillance is crucial to address potential issues such as:

- Residual or recurrent coarctation.

- Systemic hypertension.

- Associated cardiac or vascular anomalies.

25.9 Prevention and Genetic Considerations

Since CoA is a congenital defect, prevention strategies focus on early detection and management. Prenatal ultrasounds can sometimes identify CoA in utero, especially in high-risk pregnancies. Genetic counseling may be beneficial for families with a history of congenital heart defects or syndromes like Turner syndrome, which are associated with a higher risk of CoA.

25.10 Conclusion

Coarctation of the aorta is a significant congenital heart defect that poses challenges in diagnosis and management, particularly in infants and young children. Advances in medical and surgical interventions have greatly improved outcomes, but timely recognition and treatment remain critical. Long-term follow-up and a multidisciplinary approach involving pediatric cardiologists, surgeons, and primary care providers are essential to optimize the health and well-being of affected children.